Optical interoperability: Can't we all just get along?

Different network elements from a variety of vendors must not only work together, but also play well with the existing equipment that attaches to the optical network.

RON FANG and DOUG GREEN, Ocular Networks

DWDM systems owe much of their success in long-distance networks to the fact that existing SONET equipment could run over them without undergoing changes. In theory, DWDM systems simply replaced fiber, while the systems that ran over it operated as usual.In practice, many first-generation DWDM systems required that both the DWDM and the SONET gear came from the same vendor. Even in systems that allowed multivendor attachments, the presence of optical noise made it difficult for some SONET gear to understand the output of other vendors' DWDM equipment. From a business perspective, this arrangement was severely limiting, because carriers were locked into a single vendor. Based on demand from customers, DWDM equipment vendors introduced transponders and transceivers to resolve these difficulties by isolating the external systems from the need to deal with issues like optical noise and wavelength control.

However, as DWDM moves beyond the long-distance network and new elements-crossconnects, DWDM rings, and software-are added, the issues surrounding interoperability become increasingly more complex than simply emulating fiber effectively. Different network elements from a variety of vendors must still not only work together, but also play well with the existing equipment that attaches to the optical network.

Interoperability can be like salt-the right amount makes everything taste better and last longer, but too much can give you a heart attack. As is the case with optical systems, technical purity must be balanced with business needs for efficiency and profitability.

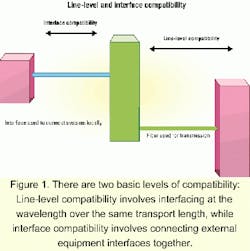

There are two basic levels of compatibility: line level and interface level (see Figure 1). Line-level compatibility involves interfacing at the wavelength level over the same transport length, while interface compatibility involves connecting external equipment interfaces together.Since line-level compatibility allows a service provider to freely interchange equipment from multiple vendors, in effect turning SONET gear into a commodity, it has been a desirable goal since the initial introduction of SONET. For years, the SONET Interoperability Forum attempted to bring about multivendor interoperability at the line level, but very few service providers today put more than one vendor's SONET gear on the same ring.

The purely technical objective of line-level interoperability has to be balanced with business needs. Line interoperability, while possible, involves reducing each vendor's function to the least common denominator. Most service providers conclude that single-ring compatibility, while a noble goal, is too costly in terms of lost function, management headaches, and the potential for vendor "finger pointing." Today, service providers typically connect SONET rings-built from different vendors-together, but seldom mix vendor equipment on a single physical ring.

Efforts to drive line-level compatibility of DWDM systems have proven equally unsuccessful. The International Telecommunication Union (IT) first attempted to establish compatibility standards by defining standard wavelengths for use in DWDM systems. To be fair, the IT designed these standards not only to promote interoperability, but also to serve a broader purpose. Nevertheless, the IT's efforts have done little to foster compatibility between systems at the line level.

The business need to optimize price and performance on DWDM systems requires that vendors leverage proprietary methods to lower cost and raise performance beyond that covered by such standards. For example, 50-GHz channel spacing was introduced in leading-edge equipment at a time when the IT standard supported only 100-GHz spacing. The definers of the standard simply hadn't anticipated technology would advance so rapidly. From a business perspective, customers could not forgo the ability to more than double the capacity of their existing systems for the sake of standards.

Today, optical technology is advancing faster than ever, and service providers are quickly adopting new technologies that increase bandwidth and reduce costs. Optical-networking equipment developers, like their SONET predecessors, squeeze the most out of their systems by developing better ways of locking lasers, detecting signals in the presence of optical noise, and balancing power.

Proprietary encoding schemes such as forward error correction enable increased drive distances that reduce regeneration costs. Compatibility at the physical transmission level requires the elimination of such added value to reach the lowest common denominator, relaxing specifications to the point where too much function is lost.

This loss of functionality comes at a time when service providers are demanding more capacity, longer distances, and lower costs. The business needs and fast advances in technology are, at least for the time being, in conflict with system compatibility at the line level.

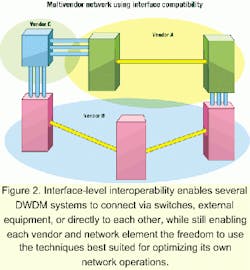

If the lessons of SONET tell us that physical-level compatibility is not always practical, they also tell us that multivendor compatibility at the external interface level is a business necessity. With interface-level interoperability, DWDM systems can connect to each other, to switches, and to external equipment-all while each vendor and network element remains free to use the techniques best suited to optimizing operations of the portion of the network it owns (see Figure 2).To date, the most successful optical-networking vendors have opted for the fastest path to interface interoperability by using existing, well-defined SONET interfaces. That way, compatibility is possible not only between multiple vendors and network elements (for example, DWDM systems and switches), but also, by definition, with the existing SONET network.

Not surprisingly, the next interface gaining widespread acceptance for connecting to optical networks is Gigabit Ethernet, another well-understood and existing standard that provides support for existing enterprise networks and routers.

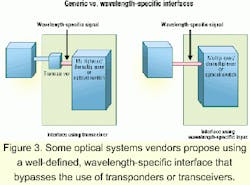

Some optical systems vendors propose using a well-defined, wavelength-specific interface that feeds directly into the multiplexer/demultiplexer stage of a DWDM system or directly into the fabric of an optical switch. This interface, similar to those used in the original single-vendor SONET/DWDM closed systems, bypasses the use of transponders or transceivers (see Figure 3).Since this interface eliminates the need for a transponder or transceiver, it saves on cost. However, it opens up issues similar, in part, to those in line-level compatibility. Not only must the wavelength be specific, but other parameters such as interface power levels must also be tightly controlled.

Because such a complicated level of compatibility is required, these interfaces are most often used when a single vendor owns both pieces. Otherwise, compatibility will almost always require relaxed standards and result in both diminished performance and profits.

Optical systems vendors often give little attention to management systems compatibility. For most service providers, however, the operational costs associated with installing, configuring, and maintaining their networks actually exceeds their capital equipment amortization. Large service providers invest heavily in their network management and testing tools, requiring new equipment to operate with existing systems.

Though the rigid standards open up large carriers to criticism, they are necessary for building large, multivendor networks while maintaining the quality of services delivered. For this reason, many first-generation management systems for optical-networking equipment (based mostly on simple network-management protocol used in data networks) are either being replaced by or integrated with TL-1 and CORBA-based systems, which are compatible with existing transmission network-management systems.

The debate continues over the benefits of buying the entire network from one vendor to achieve optimized end-to-end networking.

On the vendor side, this argument is driven by the battle between startups developing best-of-breed solutions and large companies trying to leverage broad product portfolios.

On the customer side, the debate is fueled by several factors. Carriers need to implement the most cost-effective technology to remain competitive. At the same time, they must balance their need to reduce dependence on a single vendor with the overhead costs of working with too many vendors.

As a practical matter, large service providers will always want interface compatibility, regardless of which vendor's equipment they purchase. Buying multiple network elements from the same vendor for business reasons is one thing, but creating a dependency on that single vendor-putting the service provider at technological and financial risk-is quite another.

Optical systems interoperability at the line level has been pursued both in SONET and in DWDM-based systems. The business needs to optimize profitability by "pushing the envelope" in optical systems design has rendered line-level compatibility impractical.

Interface compatibility, however, is a non-negotiable requirement and can be achieved easily with the use of existing standardized interfaces, such as SONET and Ethernet. From a business perspective, that allows service providers to not only optimize segments of the network using a single vendor's equipment, but also to reduce the risk of depending on a single vendor for all parts of the network.

Dr. Ron Fang is chief technology officer and Doug Green is vice president of marketing at Ocular Networks (Reston, VA). They can be reached via the company's Website, www.ocularnetworks.com.