Component Darwinism: Surviving the shakeout

Years from now, business school students will analyze the great telecommunications bubble. Industry lifecycle models point to many different explanations, but lessons from past industry shakeouts appear eerily recognizable. In the wake of a few hundred startup casualties, we predict the top 25 surviving optical and communications IC vendors will dwindle to just three or four companies by 2006. (Just remember, there were over 500 computer companies in 1985.) So the question everyone wants answered is: Which companies will survive?

The telecom bubble is no different than all the other boom and bust cycles: Dutch tulip mania, the English South Seas bubble, the Mississippi Company bubble in France, the great crash of 1929, Japanese real estate in the late 1980s, and the more recent Internet crash. A common precursor to most of these crises involved financial liberalization, failed due diligence, and significant capital market expansion. It's a textbook case of what happens when an unsustainable glut of new, easily funded entrants is attracted to a market at a rate that overshoots the industry's long-term carrying capacity.

The magnitude of the telecom bubble is significant, however, by historical standards. It's larger than the collapse of the railroad industry in the 1890s. Telecommunications lost over $2 trillion of paper value off peak valuations in the second quarter of 2000. The industry will take several years to fully work through the excesses of the past just to reach equilibrium.

While the conditions we're experiencing are intimidating, they also offer opportunities to those keeping their heads. Downsizing is today's agenda, but now is also the time for CEOs to reformulate long-term strategies. Sir Charles Darwin (1809-1882) came up with the theory about the Evolution of the Species by mutation and natural selection. Darwin´s rule about the "survival of the fittest" will ultimately work in favor of our industry and contribute to a successful evolution.

So we pose one question to every CEO and board member: What must the component industry recognize and do now to become healthier in three or four years? Here are some of our opinions.

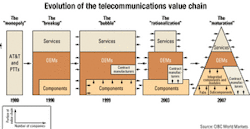

Consolidation will mostly occur through attrition or death, then mergers and acquisitions (M&As). It's inevitable that tight times will push the component sector into the realm of natural selection. Consolidation will occur among industry insiders and as outsiders look for a way in (Intel). Already, Agere Systems, Marconi, Nortel Networks, and ADC have exited the business. We believe the entire "food chain" will be disaggregated, renewed, and refocused. By 2007, most of the industry will be assimilated into a focused, pyramidal equilibrium state (see Figure). Down the food chain, company breadth will be greatly reduced. Much like the automobile industry, we suspect there will be room for small, focused component specialization and outsourcing opportunities. Right now, every company looks like a startup.

Large component vendors may benefit most. JDS Uniphase (JDSU) looks like a survivor with its strong balance sheet and product breadth. But as evidenced so far this year, the company is very guarded with its cash—as it should be. Its only acquisition—Scion—was done to phase out the more costly, arrayed-waveguide-grating program at Piri. In communications ICs, Broadcom continues to outperform its peer group, garnering a premium valuation that could be used for future acquisitions.

Which companies will challenge the JDSUs and Broadcoms for the top slots? AMCC will surely be there along with PMC-Sierra. Marvel also has a strong relative position in the industry. Multilink, Quake, and Zarlink offer good technology but may need to find partners. Now that Nortel looks to have sold its component business and Corning's component unit is ailing, a strong number two player has yet to emerge in the optics sector. Bookham Technology? Hitachi? The horse race will start to take shape shortly, and we are not sure Intel won't be at the starting line. Intel's acquisitions to date have been very puzzling—why spend all that time and risk with a rollup when Intel can sit back and take out the largest vendors like a PMC, AMCC, or JDSU quite easily. Bets anyone?

Be patient with larger acquisitions. All of this speculation is hampered by the fact that the market is still in turmoil. The problem with making large acquisitions today is that buyers don't yet know what they're buying. Risks are too great. Large consolidations may not occur until every player more fully completes restructuring activities and provides solid evidence their technology prowess is still there and capable of future market share gains. Fundamentals are also in question. With 40%-plus gross margins, we like the communications IC vendors. Where will JDSU's gross margins really fall out? Can Finisar really cut its research and development expenses and sustain acceleration of design wins? Large, diversified communications IC vendors such as AMCC, PMC-Sierra, and Broadcom may show true earnings power—well before the optical companies do.We also think enterprise-focused companies may rebound sooner than telecom vendors and may look to consolidate. We believe Agilent Technologies' transceiver group, doing over $125 million a quarter, should spin out and emerge as an enterprise consolidator, first looking at the Fibre Channel markets and companies such as Stratos Lightwave, Finisar, and privately held Picolight. JDSU's acquisition of IBM's short-haul transceiver business does not give it the needed size ($20 million per quarter) to attack this market. We could see JDSU further advance in the enterprise and storage markets.

Lastly, we need to keep in mind many Asian-based manufacturers—a Sumitomo or Fujitsu could enter the foray. Furukawa is not a likely entrant while they battle last year's acquisition of Lucent Technologies' fiber businesses.

Ask a few "what if" questions. What if Cisco Systems' acquisition strategy puts it deeper in the telecom markets? After the dust has settled and its core enterprise business turns the corner to growth, in our opinion Cisco will enter the telecom equipment space in a more formidable manner. Cisco only gets 10% of its revenues from telecommunications today. Hence, vendors should think about serving Cisco's needs on the enterprise and telecom front. The same is true of a potential merger between Alcatel and Nortel. OEM consolidation will likely trigger consolidation among optics and IC vendors.

The wave of consolidation may not emerge until 2003. Most of the major component suppliers like Agere, JDSU, and AMCC are heavily focused on facility closures and divestitures. Many CEOs have their hands full and will only consider acquisitions in limited cases. We believe the imbalance between buyers and sellers will result in numerous stranded assets. Lots of good intellectual property will "die on the vine." When component companies do start to evaluate M&A activity, they typically merge for any number of reasons:

- Complementary resources—when a company like Ford acquires Jaguar.

- Geographic coverage—when a Japanese vendor buys a U.S. vendor.

- Product expansion—when a communications IC vendor buys a laser-source manufacturer.

- Product integration—when a laser-driver company teams with a modulator vendor.

- Product diversification—potentially non-telecom, industrial, or test and measurement applications.

- Critical scale—when synergies can meaningfully reduce costs.

- Cash—when a company's net cash is worth more than its business.

Carriers' buying power ultimately filters down the food chain to vendors. Fewer carriers means better buying power. Therefore, fewer OEMs will increasingly gain buying power over component vendors. Bottom line: There may not be a profitable industry capable of sustaining growing equipment purchases. By our analysis, the service-provider market has four options:

- Growth in a competitive market leading to profitless business models.

- Little consolidation with continued competitive pressures coupled with little data growth.

- Consolidation toward a duopoly, but little data growth supporting top-line revenues.

- Our hopeful outlook incorporating both strong profitable data growth and a consolidating industry.

Three of the four outcomes could lead to a zero growth environment. Therefore, component growth by vendors will only be attained with market share gains and outsourcing trends by the OEMs. If it's assumed the service-provider market is in a cyclical decline, able to rebound with the general economy, we are at best looking at a 5% growth industry.

Balance sheets reign. Will a company's balance sheet outlast the worst-case capital spending drought? At the carrier and OEM level, uncertainty about the viability of certain suppliers has stalled decision-making and is resulting in defensive decisions rather than offensive strategic moves. That has been exacerbated by the continuing wave of layoffs in all organizations and managers' fears of making bad "bets."

We believe this trend favors legacy suppliers ; however, no organization is truly immune to survival concerns. As a result, it is critical that all organizations have the balance-sheet strength necessary to weather the storm. According to the CEOs and chief financial officers we've met, they will only seriously consider suppliers that have a stable of viable customers and enough cash to get them into 2004.

Review your pricing strategy. Customers at any cost seems to be the mantra of many executives, although lousy pricing is always blamed on "the other guy." In game theory, a Cournot model simply tells us that component prices will fall as more vendors enter the market. A common occurrence, desperate startups will price simply to penetrate, showing "traction" to their venture capitalists despite profitability.

Leaders like JDSU may also wish to rationally underprice the startup competition. Using aggressive pricing, we suspect JDSU could adopt a "last survivor strategy," leveraging its balance sheet and broad product portfolio, and try to be one of the few companies to remain standing after others disappear in a shakeout.

Structure the business for customers. Declining volumes and fewer customers are driving component CEOs to ensure broad product lines meet the breadth of their customers' needs and drive down production costs with the goal of operating as low-cost, high-volume suppliers. Component technology that was once deemed a core competency, or differentiator, by an OEM is now often viewed as a commodity. OEMs are rapidly pushing for product standardization and multisource agreements (MSAs).

As standard designs emerge, opportunities for innovation decline, but manufacturing economies of scale advance. Small startups with a business model chasing every new MSA could be disastrous. Instead, leverage existing OEM relationships. What assembly or module-level product can a company perform for these OEMs? Remember that one of the only sources of growth in the industry may come from outsourcing traditionally captive products.

Research potential new customers. It's naive to think a company's biggest customer last year will be its biggest customer in 2005. It's also naive to believe large incumbent OEMs will be the winners in the next design cycle.

It's important for component vendors to bypass OEM customers and get direct access to carrier-level diligence. Remember that the OEM sector will go through consolidation also. Tier one carriers are moving to fewer established vendors. As exhibited by Tellabs' acquisition of Ocular and Alcatel's acquisition of Astral Point, the majority of future M&A activity among the OEMs will be customer-driven, directly or indirectly. Likely OEM consolidators include Cisco, Tellabs, Alcatel, and Ciena. AT&T may soon force the consolidation of long-time OEMs.

Component suppliers must do more for less. OEMs cannot remain vertically integrated; these companies will likely outsource most of their hardware to modular-focused component vendors and electronics contract manufacturers. OEMs have generally reduced their in-house systems integration capability due to their outsourcing initiatives and are looking for higher levels of device integration to reduce module costs and improve product performance. That is leading to increased integration between communications ICs and optics (note recent moves by Intel and Vitesse).

At OFC last March, we spoke with many of the new transponder and transceiver players looking to capitalize on these integration drivers. Unfortunately, we fear that many of these component suppliers do not fully appreciate the difference between optical-device "integration" and "packaging." As the systems OEMs consolidate their suppliers, there will not be room in the market for suppliers to "stack" margins by merely offering simple packaging and design services. In the long term, the market will only support a limited number of truly integrated high-volume, low-cost suppliers.

Learn the investment banker psyche. We cannot forget the other side of the Chinese Wall, or the psyche of the investment banker. It's a bear market, and times are tough for investment bankers. They are hungry. Since the IPO market has dried-up much of the banking efforts, Wall Street is now focused on the fees generated by M&A opportunities. As always, CEOs need to use bankers as a resource and for idea generation, not as strategic advisors. The industry will consolidate, but there will be specific paths and timing for specific companies.

Acknowledge the venture capital (VC) paradox. Venture capitalists are now caught with large equity stakes in failing component businesses, but amazingly, venture money is still out there. There is a tendency not to liquidate the optical startup with $50 million in cash and no product traction, because typically the capital gain on a VC firm's investment can only be determined when the startup is liquidated or sold. (Here, we're acknowledging a hindrance to natural selection.) The venture capitalist would rather take the chance of merging the startup with another company with product traction and no cash or take the pre-bubble attitude of building a company over five years. Lastly, to be out of the telecom space now just because it's awful would be foolish at current valuations.

Open up to a "merger of equals." Most component vendors are simply not big enough to ensure a lucrative future. A merger of equals is characterized by pre-merger negotiations between two firms of similar size that result in approximately equal representation in the merged firm. These deals are usually defined as "friendly" mergers. The basic premise is whether the overall value created by the merger of equals is greater than each company operating independently (accretion). In today's environment, that accretion may be in reduced operating losses or cash burn.

Social issues such as CEO egos, location of headquarters, company name, and plans for business restructuring often prevent these types of mergers. Look at the issues surrounding the failed merger between Avanex and Oplink. For these same reasons, negotiations of mergers of equals take longer to complete after announced than mergers of non-equals and are more complex. We will surely witness dozens of mergers of equals in the coming years.

Rationalize R&D: Legacy versus next-generation components. Ironically, most executives are heavily committed to sustained R&D spending, despite an overall focus on cost reduction. Among the biggest component vendors, R&D spending as a percentage of revenue has grown from 14% in 1999 to an estimated 35% in 2002, yet most executives seem to view this spending as a sacred cow, refusing to cut it. Companies must learn to "eat their own young."

The heavy emphasis on service and support capabilities favors legacy vendors like JDSU, Agere, AMCC, and PMC-Sierra due to their large installed base and breadth of product. Repeatedly, we have heard senior executives at the OEMs say they "don't have the budgets to look at the 'startup's' components." Ironically, however, we sometimes hear these same executives complain that their legacy vendors "don't have anything new they want to buy." We believe the net effect of these two countervailing forces will be the beginning of a small wave of "arranged marriages" by OEMs selling off in-house component units, seeking to support legacy suppliers and ensuring a viable ongoing source of components. We have our own concerns that R&D spending needs to be matched to actual customer demand and would caution companies away from spending too heavily on "R" and instead focus their scarce capital on customer-driven "D."

Jim Jungjohann is managing director, communications components equity research, at CIBC World Markets (Denver).