Fiber in Europe

Stokab: The Stockholm challenge for dark-fiber provisioning Sweden's capital has launched an aggressive experiment in infrastructure provision.

By Edward HarroffIn 1993, Sweden entered in the European Union and decided to enact the most liberal telecommunications regulations in Europe. Most industry analysts consider Sweden to be advanced within information-technology (IT) applications, topping all global statistics in per-capita figures for telephones, mobile phones, personal computers, professional computers, Internet connections, and bandwidth.

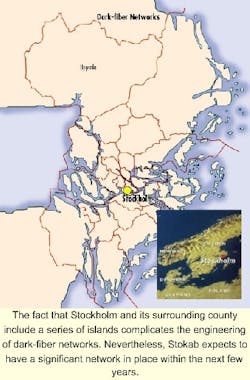

As would befit the country's capital, Stockholm has taken a lead role in ensuring that adequate fiber-optic infrastructure is available to support contemporary communications re quirements. According to Carl Ceder schiold, the city's mayor, "The local political powers want Stockholm to become a meeting place for 'new-economy' entrepreneurs and practitioners." Local government established Stokab as the vehicle to enable access to dark-fiber-optic network capacity for all IT players in the Greater Stockholm area. Stokab is fully owned by the city of Stockholm and the Stockholm County Council (see Figure).

Seven years ago, broadband communication was a rarity, reserved for large companies. Today, it is a reality for mid-sized companies in Europe and gaining interest among communication-intensive small companies. Products and services can now be found at prices that will even introduce broadband communication into the home.

In one or two years, the entire market will have to face making the gigantic changes necessary to adjust to a much greater traffic capacity than today, supplied via the next generation of Internet (e.g., Internet 2). Users will have personally selected television channels-always on and connected to various communications (telephone, fax, and data), e-commerce, and search services. According to recent Yankee Group findings, each individual will require a couple of megabytes-per-second capacity to cope with that amount of traffic.

The access technology used to connect the Swedish end customer will vary from case to case. Alternatives available will include fiber optics, radio, and various kinds of asymmetrical digital subscriber line on copper cables. However, fiber appears to be the most promising alternative when it comes to transferring traffic along the backbone networks of the future. In one or two years, there will be fiber just some hundred meters from all places of work and homes in the Stockholm urban areas due to Stokab's network-deployment strategy.

According to a 1999 Traficia report, "City Fibre in Europe," which surveys eight cities including Stockholm, at least 20 pan-European telecom operators are actively competing to link into key metro networks. "The city-based fiber network is analogous to an urban railway system on which a number of competing rail operators are licensed to run trains," says Nicola Ainsworth, head of the legal-services practice the Philips Group (Traficia is the publication trademark of The Philips Group). "Stokab is providing the dark-fiber infrastructure over which many other carriers provide different services to cater for different categories of customer."As usual, the Swedish approach to urban planning means giving lots of attention to its islands capital, Stockholm. Sweden is known for its extremely socialist public policy, so true to form, the Swedes have chosen a model that is radically different from other cities, such as London, where the survival-of-the-fittest capitalist doctrine has every potential service provider digging up the streets. In Stockholm, the city has reign over the local loop.

The major experiment in Stockholm will probably be followed throughout Sweden and beyond into other Nordic cities. Anders Comstedt, Stokab managing director believes that "we are preparing Stockholm for next-generation business, education, service, and leisure activities. For a prosperous interactive future with video phones, cyber shopping, distance working and learning, dedicated TV, and home-movie transmissions-plus all the virtual realities that we have not yet seen."

As an alternative, an open fiber infrastructure promises to be a cornerstone in the dynamic telecommunications market of tomorrow. The question of how and under what circumstances fiber is to be brought closer to the customer and of how to solve the problem of those final meters will remain open for some time.

The European Commission's "e-Europe" initiative, which was proposed by EU Commission President Romano Prodi in December 1999, is de signed to en sure that mem ber states are fully en gaged in promoting local-access competition and thus enabling more broadband infrastructure. Like most broadband infrastructure providers, Manuel Kohnstamm, vice president of corporate development at United Pan-European Communications (UPC), argues that "the Commission's challenge demands the creation of real competition between telephony, cable, wireless, mobile, and satellite networks to provide genuine choices for the European consumer."

With increased local-loop competition emerging gradually-and with a whole range of financial and technical issues yet to be resolved-it is appropriate that network operators stop to consider the risks as well as the potential gains in the local-access markets. Barry Flanigan, a consultant at research firm Ovum Ltd. (London, UK), points out that "the demand for bandwidth will fail to grow in accordance with the amount made available by the recent long-haul network builds. Instead, there is real concern that there will be short-term inability to deliver broadband services, especially to smaller businesses and households, because of regulatory, financial, and technical barriers in the local loop."

Stokab set up operations in 1994, at a time when Sweden had just begun to liberalize its telecommunications market but when it would still take a few more years before the majority of European countries would follow suit. A Traficia report noted that London and Paris were also quick to build major dark-fiber capacity.

Stokab has been operating in a market that has been undergoing constant change. "Stokab's simple business concept, which was at first looked on somewhat dubiously by some people, is now a natural part of the telecommunications market in the Stockholm area," points out Comstedt. "Stokab has been rolling out a fiber-optic network in order to stimulate multiple investments and to innovate new telecommunications services in the Stockholm region. The simple strategic decision, passed when operations begun, was that Stokab should only offer the market the fiber-optic infrastructure, i.e., dark fiber, and leave the services and new service developments to the telecommunications companies. This decision has been of great importance to the business and will constitute our guiding star in the years to come."

Work on developing the network was begun to satisfy commercial district needs, first in the center of Stockholm and then gradually out into the surrounding areas. Soon, Stokab will have at least one point of presence in each municipality in the Stockholm County, covering an area of 6,490 square km. Even now, there is a more or less completed network in most municipalities.

The main characteristics of the latest development are in line with Stokab's original plans. As a result of regional development, Stokab is now of importance to businesses throughout the county to create increased competition. Stokab's importance as a cost-efficient dark-fiber provider has even been accepted by the incumbent operators (i.e., Telia and Tele2). There are currently more than 30 telecommunications operators using Stokab's network.

Expansion of the fiber-optic network began in the commercial districts of central Stockholm and the large industrial areas around Stockholm. By 1999, the network covered most of the central city. The public schools and institutions (libraries, district administrations, etc.) as well as several industrial and business centers in the Stockholm area also will be connected. Most of the large hospitals in Stockholm County are connected to each other via the network. Several of the larger islands in the Stockholm Archipelago and Lake Mälaren have connection points to the network, which, among other benefits, makes telecommuting possible.

All municipal centers in Stockholm County had at least one access point by mid-1999. Currently, Stokab has more than 2,200 km of fiber-optic cable with a total of 154,000 km of fiber.

From an investment viewpoint, Stockholm's local governments have invested more than $100 million and are even generating a small profit from the Stokab operation. Comstedt points out, "Stokab public investors were committed to keeping Stockholm a bleeding-edge technological pole in the Scandinavian region, hence a top European player for broadband communications. With our extensive dark-fiber network completed early on, Stockholm has been able to attract lots of high-tech investments, which contribute indirectly to funding the Stokab infrastructure through their local taxes and generating paying traffic on the network."

By Stephen Hardy, Editorial Director and Associate Publisher

While local governments around the world have increased their interest in building dark-fiber networks to spur the local economy, the private sector has also targeted metropolitan areas as an emerging market for ready-made infrastructure. For example, Metromedia Fiber Network (MFN-New York) has announced its intention to expand its current infrastructure in Germany to include a total of 16 cities throughout Europe. The new network will exceed 625,000 fiber-km and 2,160 route-km that MFN will distribute among Amsterdam, Berlin, Brussels, Cologne, Dusseldorf, Frankfurt, Geneva, Hamburg, Hanover, London, Milan, Munich, Paris, Stuttgart, Vienna, and Zurich.

MFN has already made a name for itself in the United States as one of the few alternatives to the regional Bell operating companies (RBOCs) for metropolitan-area dark fiber. Pam Heller, who heads the company's European marketing efforts out of Amsterdam, reports that the competitive situation in Europe is more complex than in the United States. Certain PTTs have more dark fiber available for sale or lease in their areas than the RBOCs have in theirs. In addition, European carriers such as COLT and the regional arm of MCI WorldCom will also make fiber available to customers under certain conditions. MFN plans to combat such competition by supplying newer fiber than the PTTs and making such infrastructure more readily available than COLT and MCI WorldCom.

Heller reports that the potential customers for MFN's new dark fiber-carriers, Internet service providers, broadcasters, and large institutions-have done a good job overall of keeping tabs on the opportunities presented by the availability of dark fiber, so establishing a demand for their services in Europe has not required significant customer education. But actually building the networks can sometimes require more patience and cooperation with other parties than in the United States. That is particularly true where local authorities require "co-trenching," a scenario where multiple carriers must dovetail their schedules and requirements to lay their cables in the same trenches at the same time to minimize disruption to the community.

Heller reports that the new fiber installations have already started; MFN expected its first London customers to be online by the end of last month. To bring further value to its local offerings, MFN has reached agreement with Viatel to provide connectivity among 14 of its 16 target cities. Milan and Vienna are the two cities currently on their own; Heller says that attaching these markets to the Viatel-provided backbone sometime in the future would not come as a surprise to her.