Back to basics: Optical-network management

With an unprecedented downturn in the industry, service providers are dealing with the pain of having to do more with much less. The issue is massive cuts to capital expenditures (capex) and operating budgets.

It's no longer about which service provider has the highest market cap; it's about life or death competition for customers and service revenue. Profitability— and therefore sustainability—is the number one goal. It is a dramatic change from two or three years ago, but frankly, it's just the basics of business for any other industry.

It has become clear that there are tremendous opportunities to make improvements to operational support systems (OSSs) that will improve the efficiency and manageability of the network. New networking equipment, with the right management tools, can now offer substantial capital as well as operational cost savings.

As service providers have found that their new business reality is merely about good business, optical systems vendors have found that network management tools can have the most value by focusing on the basics of managing a network. It's simply a case of focusing on the details of network operations and fixing the problems that are having the greatest impact. It's back to basics for OSS deployment.

Before service providers ever look at the element and network management systems (NMSs) from an equipment vendor, they take a close look at the network elements (NEs). No matter how advanced the networking technology, service providers do not buy equipment that is difficult to manage on the floor. Additional requirements for either training or new operational procedures must be kept to a minimum. It's a pretty tall order for innovative new equipment.

In reality, it's just a matter of strategy to achieve an easy-to-manage networking system. Equipment vendors are very concerned about product differentiation and innovation but have to be careful not to take it too far. NE operations are one such area where conformity is better.

Take management interfaces as an example. In the transport world, TL-1 has long been the human and machine interface of choice. Operators have been using it for years, and a great deal of OSS infrastructure had been built around it. Nevertheless, equipment vendors have implemented a series of machine interfaces such as simple network management protocol (SNMP), Common Object Request Broker Architecture (CORBA), and common management information protocol/common management information service element (CMIP/CMISE) as well as a host of human command line interfaces.

Although there are technical advantages and disadvantages to any protocol, it's really an operational question. From this perspective, it's obvious that transport network equipment has to have a standards-based TL-1 interface. If the network equipment is innovative to the point of being nonstandard, TL-1 can still be used. Operator training time is limited to the new commands and hopefully the capabilities of the new equipment.

That doesn't mean SNMP and CORBA don't have a place as management interfaces in optical networks (although we can probably wave good-bye to CMIP/CMISE). To maximize OSS interoperability and satisfy diverse worldwide customers, equipment vendors must support multiple interfaces. In the past, new interfaces were added as an afterthought due to customer pressure. Equipment vendors are now implementing their software from day one with the ability to run multiple interfaces alongside a TL-1 interface. The key is to provide a layer of abstraction between the external interfaces and the internals of the system. As a day one design decision, new management interfaces, or even customized interfaces, can be added quickly and at minimal expense.

Examining the changes in off-board management systems, we see that trends in element management systems (EMSs) are closely tied to the networks elements. As long as the NEs are operationally efficient, the EMS's role is to automate tasks and streamline procedures. Even the best EMS cannot compensate for operationally inefficient NEs. Operations can no longer be considered an after-thought in the design of new networking equipment.

For example, some optical-networking equipment can support multiple speeds and protocols (SONET/ SDH, Gigabit Ethernet, Escon, etc.) by collapsing functions into a single NE. Although these NEs are all conceived with the intent to save capex, only those NEs that do not require interface-card changes to run a different signal have the ability to reduce operating expenses (opex). Adding the management system and management interfaces to enable remote changes eliminates truck rolls for changes in service.

Similarly, element management is a tool to unlock remote testing and diagnostic capabilities of the NEs to reduce truck rolls and reduce service downtime. Equipment today must provide enough loopback capability to isolate failure—not only to a particular network element, but also to a specific card within an NE.

The EMS provides the capability to remotely set up, tear down loopbacks, and run diagnostics. It will even provide interpretation of results to streamline problem resolution. Guesswork and investigation time on the floor is minimized. With operations-focused on element management, new types of NEs are reducing opex for service providers by becoming easier to manage than their predecessors.

Over the past few years, while the large vendors were busy building comprehensive integrated OSSs, many startups were taking the opposite approach. Their network management offering was limited to a bare bones element manager. The failure of these two opposing strategies has shown that service providers need something in between.

Optical-networking systems vendors are now providing integrated element and network management solutions that allow the user to move seamlessly from a network to an element management view (see screen shots). Done in this fashion, these systems can provide operational value for the equipment they manage.

For example, as optical networks evolve from ring to mesh (and hybrids of the two), visualizing end-to-end connectivity is important for provisioning, monitoring, and maintaining service. An integrated system within a wavelength network gives the user the ability to view an end-to-end light path from a user console. While viewing the route a path takes, the user can zoom in on the affected NEs and clearly identify what cards are being used in providing that service. If there is a problem on that path, it is simple to locate. If there are maintenance activities planned on a fiber, the management system can quickly correlate a port, or fiber, to a list of network services.

More than just visuals, an integrated system can facilitate service delivery and maintenance activities. Consider, for example, advanced optical-networking systems that have the ability to bridge wavelengths. An integrated management system can assist the user to provision and activate end-to-end protected wavelengths using this unique capability of the network element.

It can provide the coordination to hitlessly roll the light path to a secondary route. Taken together, it means less service downtime, reduced maintenance windows, and minimal manual effort. For the service provider, that translates into reduced customer impact and improvement to the bottom line.

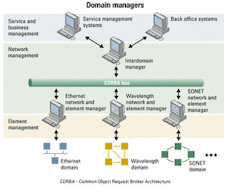

Despite these steps forward by equipment vendors, now more than ever service providers want to purchase or build their own comprehensive end-to-end NMS. At first glance, this would appear to overlap with the notion of integrated element and network management from the equipment vendor. In fact, the two are completely complementary. All that is required is the concept of "management domains."This concept divides the network management layer into a hierarchy of two levels. Above element management, domain managers provide network management functions, but only for their domain of control.

In this model, there might be a domain manager for the wavelength portion, the Ethernet portion, and the SONET portion of the network. Domain managers provide network-level visualization, provisioning, and monitoring for their domains. They also provide the conduit to the element management functions for the equipment in their domain (see Figure).A major advantage is that the higher-level NMS has to be integrated with a relatively small number of domain managers rather than dozens of element managers. The benefits are fairly obvious: Fewer integration points means less development and expense. More important, when this level of integration is simplified to such a level, it means that the higher-level systems can finally start to add the value in automating the business of operating a large multivendor, multitechnology network.

Of course,this discussion would not be complete without a quick note on interface definitions and protocols to make this model work. The telecommunications industry has made numerous attempts to define standard interfaces to integrate OSSs. What had been lacking was the massive uptake of any particular standard.

That finally may be happening with the now predominant use of the Telemanagement Forum's TMF814 "Multi-technology Network Management Solution Set." This initiative describes a CORBA interface for the management of SONET, DWDM, and ATM networks. It has had sufficient uptake by the network equipment vendor community as a de facto standard. Given that de facto standards tend to breed followers and create barriers for adopting other interfaces, it ultimately means a single model for creating NMSs.

For years, the wrath of network operators has been multivendor networks that require multiple management systems, multiple procedures, and ultimately, the dreaded "swivel-chair management." The concept and deployment of domain management and the uptake of the Telemanagement Forum models are enormous steps toward eliminating these complex systems. Equipment vendors are doing even more to make it reality.

In the past, equipment providers built businesses around networking silos. Proprietary interfaces to management systems acted as a lock to keep customers tied to a single vendor. Service providers no longer tolerate this strategy. As a result, more and more equipment vendors—particularly smaller companies eager for their first sale—are opening up their management interfaces completely. The interfaces are based on industry standards that will enable the NEs to be rapidly integrated into OSSs.

In a domain-manager type of model, the domain managers must be multivendors. That is, they must provide network and element management for a variety of NEs within the domain. Given the use of standards-based TL-1 and/or TMF814 and that these elements have similar features and functions to be contained in a domain, this model is quickly becoming a reality.

As mentioned earlier, over the past few years, equipment vendors have come and gone from selling products in the service management area. They no longer have the financial resources (or business case) to develop and sell higher-level OSS systems. It's no longer a core area of their business.

Over the same time period, the number of independent software vendors (ISVs) in this space exploded, and more recently the number of ISVs has been reduced through consolidation as well as failure. In some areas, de facto leaders have emerged.

Equipment vendors have begun working more frequently with ISVs. While sometimes the relationships are as strong as an OEM agreement, more frequently the companies work together to pre-integrate the network equipment with the service management application. The end result is that service providers can choose the best of breed application for their particular situation.

Despite moving out of the service management business, equipment vendors still maintain a keen interest in seeing their equipment integrate as seamlessly as possible with the service provider's OSS. ISV partners and open management interfaces both play a role in making that happen. Perhaps it's the mindset of optical equipment vendors that has changed most dramatically.

Now, as an early part of the sales cycle, suppliers are engaging their service-provider customers to review operational strategies and the NMSs. There is a real willingness to work together and even invest in their system's capabilities to smooth integration and ultimately for the service provider to see true economic gains.

Nowhere is that more obvious than with the Telcordia OSS systems running in the RBOC networks. In the past, companies—especially startups—would try to avoid the OSMINE (operations systems modification for the integration of network elements) process; now they clearly understand that it is an absolute requirement.

For private companies, budgets are stretched to ensure that adequate funding is available for what may be an expensive process. At Telcordia's yearly network-equipment-provider symposium this year (a conference for those companies going through the OSMINE process), record attendance was reported. Clearly, for an industry in decline, this attendance figure is an important indicator of the significance of OSMINE.

An economic downturn typically moves the power back to the purchaser. Due to intense competition, not only do costs come down, but products also change for the better. Such is the current climate for service providers and their network equipment suppliers. New network management products will have a substantial impact on service providers' operations and their bottom line.

The time is perfect for service providers to upgrade and evolve their OSS systems to take advantage of these capabilities. Perhaps the only frustrating aspect for service providers is that they have been preaching these sorts of requirements to the equipment vendors for years. Perhaps it just takes a harsh economy to make truly effective network management a reality.

Robert Gaudet is a director of product management for network management systems at Meriton Networks (Ottawa, Ontario). He can be reached via the company's Website, www.meriton.com.